Recently, Dominic Lawson, a columnist at the British newspaper the Sunday Times, proclaimed, whilst commenting on the recent [British] junior doctors contract dispute, that he had discovered the etiology of the crisis of the National Health Service. It was simply the fault of XX chromosomes. According to Mr. Lawson, there were, quite simply, too many female doctors.

He felt ‘feminization of medicine’ had resulted in less potential physician work hours because women reproduce, take maternity leave, and return to work part-time. He wrote: “Fewer women than men choose to work out of hours, and the increase in women doctors may have partly influenced the recent abandonment of out-of-hours work by general practitioners in the UK. Family life (is) an institution to which men tend to pay homage but that women are actually more likely to put ahead of their career”.

Lawson’s misguided article was extracted from several sources which included the 2008 British Medical Journal debate by senior research fellow Brian McKinstry, and the opinion of Dr Max Pemberton, a 30-something NHS psychiatrist. He wrote in his Daily Mail column last year that “women doctors could bring the NHS to its knees” with the implication that women were wrong to expect a work-life balance in medicine. Lawson also quoted Dr. Heath, a ‘NHS veteran’ who stated, “Women doctors don’t like weekend rotas…This is one of the reasons Paediatric Units are failing”.

In a prompt rebuttal to Lawson’s sexist article, UK doctors launched the twitter response #likealadydoc. This campaign provided epigrammatic demonstrations of doctors in possession of ovaries doing great work within the NHS, with equally positive encouragement by their male colleagues.

Later in the week doctors around the world posted selfies wearing pink at work to celebrate the campaign with the icon #pinkwednesday.

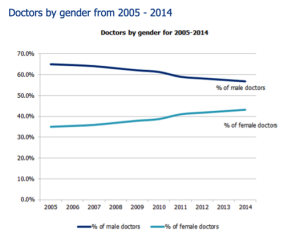

So is the NHS being drowned in estrogen? It’s true that women are becoming an increasing percentage of the medical workforce in the UK. December 2015 data from the General Medical Council demonstrates that 45% of registered medical practitioners, 32% of Consultants and 51% of General Practitioners (GP) are female. Current trends indicate that in England, female doctors will become the majority at some point between 2017 and 2022.

Female doctors are more likely to take maternity leave and more likely to return to work ‘Less than full time’ (LTFT) than their male colleagues. If you employ LTFT workers then naturally your department will need more doctors to staff the same whole time equivalent rota. So yes, overall, you will need to train and employ more doctors.

But this doesn’t sound like the cause of the NHS crisis to me. Surely it just takes a few sums for workforce planning and medical school admissions to make up for the fact that x percentage of your workforce are LTFT? If being female is a problem, why are half of NASA’s latest class of astronauts made up of women (including two mothers)?

The real crisis is unrelated to gender. Many of our NHS doctors are suffering from burn-out and ill health, leaving the NHS to work in Australasia, or leaving Medicine all together. Last year only 52% of junior doctors who finished their two-year foundation training after medical school chose to stay in the NHS to work towards becoming a GP or specialist doctor. If working LTFT can create a better work-life balance then the results will be improved staff retention, increased productivity, and care delivered to patients with greater enthusiasm and empathy.

In fact, that working longer hours per week in the NHS results in a linear increase in productivity may be a flawed concept. Research suggests that over a certain threshold of hours per week, productivity actually falls as employees experience fatigue, plus there is an increased risk of errors, critical incidents and sickness. In different industries, organisations with a large share of part-time employees have been demonstrated to be more productive than those with a large share of full-time employees.

In 2015, 20% of LTFT training doctors were male and this figure is expected to rise as both acceptance of shared parental leave increases and the work-force look at ways to develop a more sustainable long-term career.

When complaining about the reduced hours worked by LTFT doctors, in many cases they are not far off the weekly 37.5 hours worked by the lay population. And it doesn’t take two part-time doctors to cover the work of one full-timer. Most LTFT Consultants in Emergency Medicine are working 70-80% of the hours of their full-time colleagues. Many of them work significantly over their paid hours to deliver in national committees, departmental lead roles, medical education, and research. LTFT job plans normally contain the same percentage of out of hours work as their full-time colleagues. In some cases, they may actually work the same number of anti-social hours or an increased frequency because they can be at work while their children are in bed.

Using another frequently cited argument against LTFT working there are few specialties where reduced hours working would impact on continuity of care for patients. In Emergency Medicine, when we finish our shift and leave work, our patients have already been discharged or handed over to inpatient admitting teams, and in-hospital specialty Consultants more commonly work in ‘teams’ with groups of individuals looking after the same patients to cover each other when on leave.

In summary, the NHS needs to develop more effective strategies of working LTFT. It’s not about women and the feminization of the NHS. Although I think Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the first woman to receive a medical qualification in Britain in 1865, would be cheering.