I’m here to tell you my story.

Disclaimer: I’m an Emergency Physician. My story starts in the Emergency Department. In honor of patient confidentiality, this part of my story is fictional. Though this particular story never happened, though this particular patient never existed, this story represents my truth. Stories like this one happen every day.

Content warning: heavy on the feelings, so give yourself space and time and time to process.

My story starts at sign out. Everything was normal until my colleague stood up to leave and I realized that I was going to be alone. I’d forgotten to check the weekend schedule and didn’t realized that the staffing was decreased from what I was used to. I was breastfeeding, so I started to worry about how I would fit in time to pump.

“When does the next attending come on?”

“Not for a few hours. Don’t worry. The residents are great. It’s quiet. You’ll be fine.”

And for awhile, I was fine. Then a patient came in with a STEMI, and another with an acute stroke, and another after a major trauma and suddenly I was supervising a full emergency department with over forty active patients. The residents were doing a great job, but it was clear that this was too much for one attending to handle alone.

“Hey doc, can you come check on my patient? She looks sick. ”

I suppressed my annoyance at the interruption and followed the nurse back to the room in the corner, where the young woman with “typical renal colic and stable vitals waiting for imaging” had been signed out.

Instead, I saw a patient who was pale with shaking chills. Her skin was hot and her pulse was fast and thready. I realized that this patient’s simple kidney stone was now a full blown case of gram negative sepsis with an obstructed ureteral stone. If we didn’t hurry, she was going to die.

We activated our sepsis code, started antibiotics and fluids, called urology, and moved with purpose as I hoped that we weren’t already too late.

In this surprise single coverage window, I’d missed my pumping break, so my chest was aching and full of milk. As we worked to resuscitate our patient, her partner turned to me and asked, “She’s breastfeeding. Is this going to affect the baby?”

In that moment, I didn’t just burn out, I broke.

The imaginary line separating those of us in white coats from the others in hospital gowns dissolved, and I realized that I was just as human as my patient, and she was just as human as me.

I realized that I was being asked to do impossible things – to do the work of two attendings, while also acting as the primary source of nutrition for my baby at home. I was failing at all of those things as a woman lie critically ill in front of me. It all felt like my fault.

How could anyone succeed under these circumstances? How could this woman’s life depend on my ability to achieve impossible things? This was madness. Thankfully, our treatments arrived in time, and she made a full recovery.

The next day I went to talk to my boss at the time. I was angry, with tears in my eyes. “This cannot happen again,” I said. “We need to do something. We need to fix this.”

“What do you expect me to do?” he said. He shrugged and ran off to a meeting.

My sadness and fear and frustration coalesced into fury. We weren’t doing anything to prevent this from happening again. Next time, I wasn’t sure if I’d be the doctor, or the patient.

In that moment of rage and loneliness, I felt very queer. I was being asked to do the impossible and blamed when I failed and told that I was the broken one. But I knew better.

What it means to me to be a queer woman is to know what it feels like to feel totally broken and alone in the world. And then somehow, to know in the core of my human soul that I matter just as I am, simply because I exist. To know that I am worthy of joy and I am worthy of justice, simply because I am human. To know that when I am told that my joy doesn’t matter, and when my justice is denied to me, I can step into my power to take it back.

In the context of how I grew up, coming out as queer meant challenging the foundation of every relationship I ever had. Breaking them down and rebuilding. I didn’t expect to have to go through that again as a woman in medicine. What gets me through now are the tools and support that got me through the last time.

What do I do with my brokenness? What do I do with my rage? As a queer woman, I learned to come out. To tell my story.

One of the first times coming out worked was when I was 16. I was so lonely and so hopeless. I told my friend Eli what was going on. I don’t remember exactly what she said, but I remember how she made me feel. “Honey, don’t be silly. I see you and I love you, exactly as you are.” And in that moment, she healed me.

Back then, I thought coming out was something that you did once. Now I know it’s something you do forever. I’ve been coming out as queer for 18 years. But I’ve also come out as pregnant. As angry. As wrong. As uncertain. As the doctor who cries in the trauma room. Coming out is about telling the truth that’s not safe to tell, because it needs to be told. We tell each other our stories to heal, to connect, to share our collective wisdom. To say “me too.” To belong.

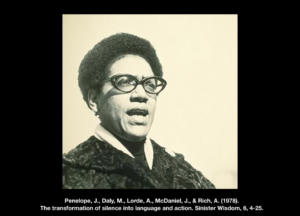

When I was trying to figure out how to tell this story, I read an essay by a renown black lesbian poet Audre Lorde called “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action.” She delivered it in 1977 as a talk at a women’s conference. In that essay, she encourages her colleagues to tell their stories, even though they are afraid.

She writes: “And of course I am afraid, because the transformation of silence into language and action is an act of self-revelation and that always seems fraught with danger. But my daughter, when I told her of our topic and my difficulty with it, said, ‘Tell them about how you’re never really a whole person if you remain silent, because there’s always that little piece inside of you that wants to be spoken out, and if you keep ignoring it, it gets madder and madder and hotter and hotter, and if you don’t speak it out one day it will just up and punch you in the mouth from the inside!’ “

I love that image. It feels true for me – I keep coming out despite my fear because I cannot bear to live in silence. I also love it because I know that her daughter, Dr. Elizabeth Lorde-Rollins, grew up to be a physician, and is one of the kindest healers that I have ever had the pleasure of working with and learning from.

Audre Lorde goes on to say that our silence will not protect us. We must tell our stories.

In Emergency Medicine we do amazing things every day. We’re also asked to do impossible things. And we’re good at that, too. We do our best with the broken systems we have, and we figure out how to make it work.

But we’re not superhuman. We cannot accomplish the impossible without breaking ourselves. It’s time to shift the paradigm. Our humanity is our strength, not our weakness.

We’ve gotten really good at making the impossible look easy. We all know that it’s not, but no one else does unless we tell our stories.

It is madness that our patients’ lives depend on us accomplishing impossible things every day. It is madness that we sacrifice ourselves in the process. We can and we must do better.

What coming out as queer taught me is that I can’t survive in silence. Our silence as healers will not protect us or our patients either.

So I’m here to tell you my story. I want to hear yours. I’m here to come out as human, because our power is in our stories.

Watch the full FIX18 talk below!

Dr. McNamara’s post can be found on her blog Joy and Justice.

Here! Here! Agree wholeheartedly.