Advancing Healthcare by Empowering Women in Emergency Medicine

Advancing Healthcare by Empowering Women in Emergency Medicine

Advancing Healthcare by Empowering Women in Emergency Medicine

Together, we will improve the careers of women practicing emergency medicine while facilitating better care for our patients.

Together, we will improve the careers of women practicing emergency medicine while facilitating better care for our patients.

Together, we will improve the careers of women practicing emergency medicine while facilitating better care for our patients.

Leadership Development

Leadership Development

Leadership Development

Our leadership programs empower women in emergency medicine to develop the skills and confidence needed to advocate for themselves and their patients.

Our leadership programs empower women in emergency medicine to develop the skills and confidence needed to advocate for themselves and their patients.

Our leadership programs empower women in emergency medicine to develop the skills and confidence needed to advocate for themselves and their patients.

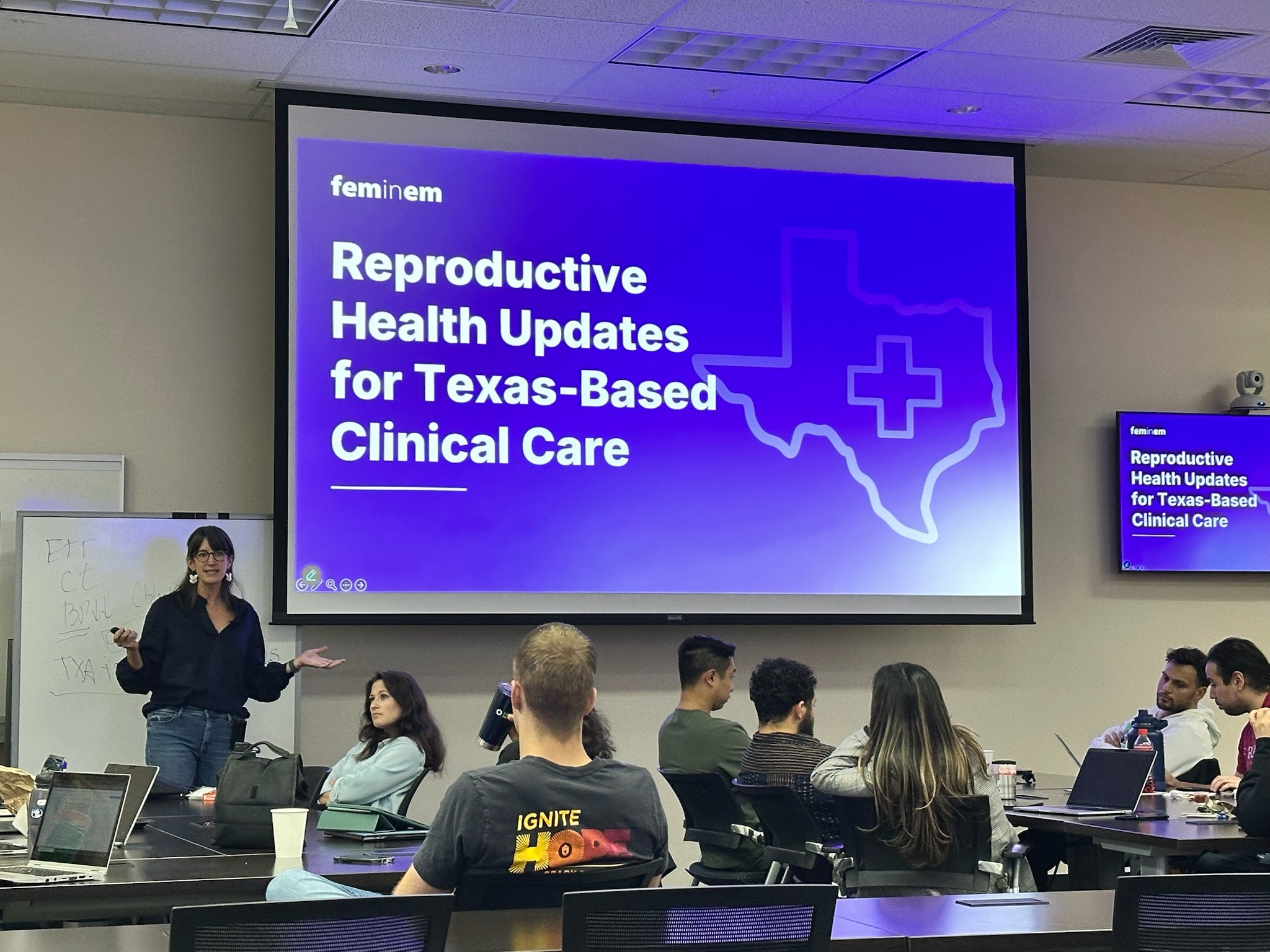

Clinical Education

Clinical Education

Clinical Education

Our clinical education resources are designed to ensure that all patients, especially women, receive evidence-based care in emergency departments across diverse settings.

Our clinical education resources are designed to ensure that all patients, especially women, receive evidence-based care in emergency departments across diverse settings.

Our clinical education resources are designed to ensure that all patients, especially women, receive evidence-based care in emergency departments across diverse settings.

Research & Collaboration

Research & Collaboration

Research & Collaboration

We champion research and collaboration focused on advancing gender equity and reproductive healthcare in emergency medicine.

We champion research and collaboration focused on advancing gender equity and reproductive healthcare in emergency medicine.

We champion research and collaboration focused on advancing gender equity and reproductive healthcare in emergency medicine.

Speakers

Speakers

Speakers

CME Hours Delivered

CME Hours Delivered

CME Hours Delivered

Learners Across 12 States

Learners Across 12 States

Learners Across 12 States

Explore Our Substack

Explore Our Substack

Explore Our Substack

An additional hub for our stories, news, and resources that helps us do our work in the ED and at home.

An additional hub for our stories, news, and resources that helps us do our work in the ED and at home.

An additional hub for our stories, news, and resources that helps us do our work in the ED and at home.

Speaker Bureau

Speaker Bureau

Discover a diverse network of seasoned experts ready to share insights on topics from leadership and wellness to trauma care and public health.

Book a speaker — or join the roster yourself!

Discover a diverse network of seasoned experts ready to share insights on topics from leadership and wellness to trauma care and public health.

Book a speaker — or join the roster yourself!

Discover a diverse network of seasoned experts ready to share insights on topics from leadership and wellness to trauma care and public health.

Book a speaker — or join the roster yourself!

Programs

Programs

for Everyone Practicing Emergency Medicine

for Everyone Practicing Emergency Medicine

for Everyone Practicing Emergency Medicine

Physician Outreach & Education Program

Physician Outreach & Education Program

Physician Outreach & Education Program

Supporting Emergency Department Physicians to deliver compassionate, legally sound, and clinically excellent care — and growing beyond.

Supporting Emergency Department Physicians to deliver compassionate, legally sound, and clinically excellent care — and growing beyond.

Supporting Emergency Department Physicians to deliver compassionate, legally sound, and clinically excellent care — and growing beyond.

Champions of Change Leadership Program for Medical Students

Champions of Change Leadership Program for Medical Students

Champions of Change Leadership Program for Medical Students

Through specialized training modules, we equip students with leadership, advocacy, and practical tools to improve reproductive healthcare.

Through specialized training modules, we equip students with leadership, advocacy, and practical tools to improve reproductive healthcare.

Through specialized training modules, we equip students with leadership, advocacy, and practical tools to improve reproductive healthcare.

Reproductive Health Care (RHC) Working Groups

Reproductive Health Care (RHC) Working Groups

Reproductive Health Care (RHC) Working Groups

Brings together emergency physicians in similar practice environments to exchange best practices and develop regionally tailored strategies.

Brings together emergency physicians in similar practice environments to exchange best practices and develop regionally tailored strategies.

Brings together emergency physicians in similar practice environments to exchange best practices and develop regionally tailored strategies.

Resources

Resources

Strengthen Your Clinical Practice and Advance Your Professional Growth

Strengthen Your Clinical Practice and Advance Your Professional Growth

Strengthen Your Clinical Practice and Advance Your Professional Growth

Clinical Resources

Clinical Resources

Clinical Resources

Evidence-based protocols that equip physicians to manage reproductive health emergencies and ensure optimal patient outcomes.

Evidence-based protocols that equip physicians to manage reproductive health emergencies and ensure optimal patient outcomes.

Evidence-based protocols that equip physicians to manage reproductive health emergencies and ensure optimal patient outcomes.

Promotion & Development Resources

Promotion & Development Resources

Promotion & Development Resources

Equips women physicians with actionable strategies for work-life balance, leadership development, and gender equity to thrive and lead in emergency medicine.

Equips women physicians with actionable strategies for work-life balance, leadership development, and gender equity to thrive and lead in emergency medicine.

Equips women physicians with actionable strategies for work-life balance, leadership development, and gender equity to thrive and lead in emergency medicine.

Stay Informed. Stay Ahead.

Stay Informed. Stay Ahead.

Stay Informed. Stay Ahead.

Get the latest clinical tools, professional development opportunities, and expert insights — delivered straight to your inbox.

Get the latest clinical tools, professional development opportunities, and expert insights — delivered straight to your inbox.

Get the latest clinical tools, professional development opportunities, and expert insights — delivered straight to your inbox.

Donate

Donate

Give To this vital work

Give To this vital work

Give To this vital work

Your generosity keeps us going. Help make a difference in reproductive healthcare in emergency medicine.

Your generosity keeps us going. Help make a difference in reproductive healthcare in emergency medicine.

Your generosity keeps us going. Help make a difference in reproductive healthcare in emergency medicine.

FemInEM recognizes the enormous leadership potential of women with emergency medicine training. Unlike other professional society meetings and leadership programs I've attended, the FemInEM conference was about making an impact on people in your community and globally by bringing your whole self as a woman and leader to the table...we're women who show up for others to ignite ideas, grow programs, and improve the world around us!

Dr. Liz Goldberg

Denver, Colorado

FeminEM advocates for more research to inform the care of women. Specifically to improve reproductive healthcare delivery in emergency departments. Women deserve the best care, based on the best evidence.

Dr. Ken Milne

London, Ontario

It was after attending my first FeminEM retreat I felt I finally found my tribe in emergency medicine. Here was a safe place to share our unique struggles, genuinely celebrate our victories, and collaborate to improve the culture of emergency medicine for other female physicians.

Dr. Breanne Jacobsilne

Washington, D.C.

In my second year of residency, I mustered up the courage to tell one of my APDs that I wanted to be an abortion provider. I felt super scared telling anyone this or saying it aloud for the first time...Pretty amazing to think this was actually the seed that was planted for me, in retrospect.

Anonymous EM Physician

Anonymous

FemInEM has been a lifeline in the storm of emergency medicine, where burnout is staggering, especially among women. This organization uniquely bridges professional development, peer support, and advocacy, tackling the root causes of moral injury and burnout that drive women from our field. By empowering women to reclaim their careers and well-being, FemInEM transforms clinicians' lives and enhances the care we provide, ultimately benefiting the patients we serve.

Dr. Andrea Austin

San Diego, California

FemInEM recognizes the enormous leadership potential of women with emergency medicine training. Unlike other professional society meetings and leadership programs I've attended, the FemInEM conference was about making an impact on people in your community and globally by bringing your whole self as a woman and leader to the table...we're women who show up for others to ignite ideas, grow programs, and improve the world around us!

Dr. Liz Goldberg

Denver, Colorado

FeminEM advocates for more research to inform the care of women. Specifically to improve reproductive healthcare delivery in emergency departments. Women deserve the best care, based on the best evidence.

Dr. Ken Milne

London, Ontario

It was after attending my first FeminEM retreat I felt I finally found my tribe in emergency medicine. Here was a safe place to share our unique struggles, genuinely celebrate our victories, and collaborate to improve the culture of emergency medicine for other female physicians.

Dr. Breanne Jacobsilne

Washington, D.C.

In my second year of residency, I mustered up the courage to tell one of my APDs that I wanted to be an abortion provider. I felt super scared telling anyone this or saying it aloud for the first time...Pretty amazing to think this was actually the seed that was planted for me, in retrospect.

Anonymous EM Physician

Anonymous

FemInEM has been a lifeline in the storm of emergency medicine, where burnout is staggering, especially among women. This organization uniquely bridges professional development, peer support, and advocacy, tackling the root causes of moral injury and burnout that drive women from our field. By empowering women to reclaim their careers and well-being, FemInEM transforms clinicians' lives and enhances the care we provide, ultimately benefiting the patients we serve.

Dr. Andrea Austin

San Diego, California